China’s rise as a maritime superpower did not happen by accident. Over the past two decades, Beijing has orchestrated one of the most ambitious and far-reaching infrastructure strategies in modern history: the construction and acquisition of a global network of commercial ports that now ring the world’s major sea-lanes. From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean, from Africa’s Atlantic coastline to the Arctic Circle, the People’s Republic has leveraged state-backed financing, commercial partnerships, and geopolitical leverage to establish a maritime footprint unlike anything seen since the height of European imperial expansion.

What emerges today is not merely a collection of ports, but a strategic architecture—a planetary-scale logistics system intertwined with diplomatic influence, commercial primacy, and latent military utility. China calls these projects trade gateways. Western analysts increasingly see them as the structural foundation of a new global order.

A Strategy Rooted in the Logic of Empire

China’s world-spanning port network traces back to two interlocking strategic imperatives.

The first is economic: a nation dependent on manufactured exports and imported energy must secure access to shipping corridors. The second is geopolitical: Beijing has long recognized that global influence flows through choke points, supply chains, and infrastructure—tools that accelerate China’s ascent while offsetting its vulnerabilities.

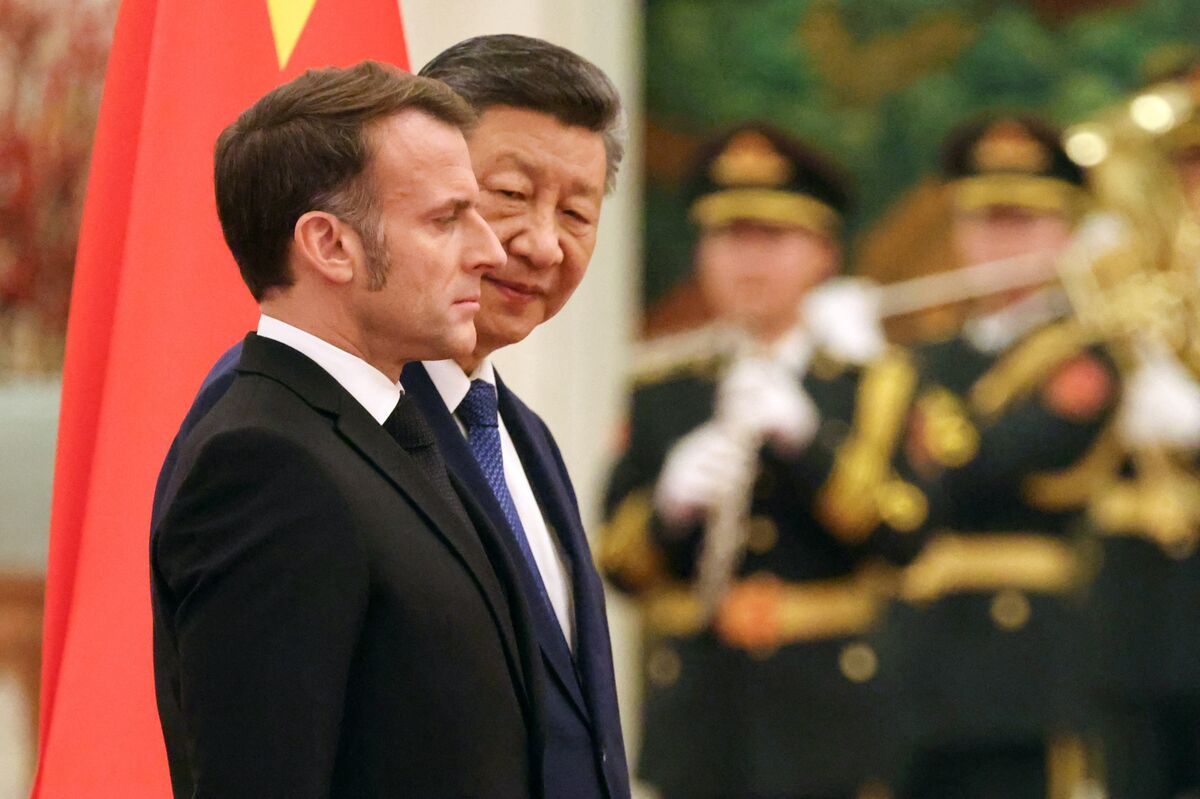

Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, became the umbrella under which these ambitions cohered. Port investments soon multiplied from South Asia to Europe. What looked at first like scattered infrastructure projects turned out to be nodes in a single, coordinated maritime strategy.

The String of Pearls: China’s Indo-Pacific Arc

China’s first major phase concentrated on the Indian Ocean, creating what analysts termed the “String of Pearls”—a chain of ports stretching from the South China Sea to the Suez Canal.

Key examples include:

- Gwadar, Pakistan: A deep-water port near the Strait of Hormuz, financed and operated by Chinese companies.

- Hambantota, Sri Lanka: Leased to China for 99 years after Sri Lanka struggled to service its debt.

- Kyaukpyu, Myanmar: A gateway to pipelines that bypass the Strait of Malacca.

- Port Sudan and Djibouti: Strategic access points for Africa and the Red Sea; the latter hosts China’s first overseas military base.

Individually, these ports serve commercial purposes. Collectively, they form an arc of strategic influence, giving China visibility, leverage, and logistical depth across critical maritime chokepoints.

The Mediterranean and Europe: China’s Western Gateway

China’s maritime ambitions expanded rapidly into Europe as its state-owned enterprises sought footholds in advanced logistics markets.

The most emblematic case is the Port of Piraeus in Greece, one of Europe’s busiest, where COSCO now controls a majority stake. Once a struggling port, Piraeus has been transformed into a major gateway for Chinese goods entering the EU.

China’s footprint also extends to:

- Valencia and Bilbao (Spain)

- Vado Ligure (Italy)

- Zeebrugge (Belgium)

- Noatum ports (across the EU)

- Infrastructure investments in Rotterdam and Antwerp

In Europe, China’s port investments have not only increased its economic presence but also created political leverage—subtle but real—over countries reliant on Chinese capital and trade flows.

Africa: The Emerging Maritime Frontier

Africa has become a central theater for China’s port-building activity. Here, Beijing’s strategy intertwines infrastructure development with diplomatic outreach and resource security.

Across the continent, Chinese firms are building or expanding ports in:

- Lagos and Lekki (Nigeria)

- Bagamoyo (Tanzania)

- Port Gentil (Gabon)

- Walvis Bay (Namibia)

- Lamu (Kenya)

These projects support Africa’s integration into global trade while ensuring China’s access to critical minerals, agricultural exports, and new markets for its technology and construction sectors.

Africa’s ports also provide China with logistical redundancy—alternative routes should tensions with Western powers disrupt access elsewhere.

Latin America and the Caribbean: China’s Western Hemisphere Play

China’s presence in the Americas is less discussed but increasingly significant. Investments in ports across Brazil, Peru, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, and the Caribbean reflect a long-term strategy to secure commodities and influence trade flows.

The controversial port project in El Salvador, as well as Chinese involvement near the Panama Canal, demonstrates how Beijing is quietly gaining strategic footholds in the Western Hemisphere—traditionally a U.S.-dominated domain.

Commercial Infrastructure With Dual-Use Potential

China insists that its port network is not military in nature, and in many cases this is true: commercial ports are designed primarily for trade, not warships. Yet the line between civilian and military use is thin. Modern naval power requires logistics, and logistics requires ports.

Chinese naval vessels already call at some BRI ports for replenishment. Dual-use infrastructure means China could, if necessary, rapidly expand its overseas military presence without building overt military bases.

In strategic circles, this dual capability is viewed as an essential part of China’s long-term plan to:

- Protect its global supply chains

- Project influence across the Indian Ocean and beyond

- Reduce vulnerability to U.S. maritime dominance

- Build capacity for blue-water naval operations

Ports are not military bases—but they make military activity easier.

Debt, Diplomacy, and Dependency

Critics accuse China of engaging in “debt-trap diplomacy”—offering loans for costly infrastructure that some countries cannot repay, then securing leverage over strategic assets. The Hambantota case in Sri Lanka is often cited, though scholars debate whether China intended to ensnare Sri Lanka or simply took advantage of the situation.

More broadly, China’s port strategy creates relationship-based dependency:

- Nations become reliant on Chinese financing

- Ports require continued Chinese management and technology

- Political elites gain ties to Chinese state-backed entities

- China’s influence deepens not through coercion, but through structure

Even where debt is not a major factor, the scale of Chinese investment shapes the strategic outlook of partner countries.

A Geoeconomic System—Not Just Infrastructure

What China has built is not a series of disconnected ports, but a global supply-chain architecture:

- Maritime routes through Asia and the Middle East

- Overland connections through Central Asia and Europe

- Ports in every major region

- Digital platforms linking logistics, customs, and payment systems

- Energy infrastructure integrated into trade corridors

This system positions China at the center of the world’s physical infrastructure—just as Western technology giants sit at the center of the world’s digital infrastructure.

In both domains, control follows scale.

The Strategic Implications: A New Maritime Order

China’s port network signals a profound transformation of global power:

- Economic Advantage

Control over global logistics increases China’s leverage over trade patterns and supply chains. - Political Influence

Countries hosting Chinese-built ports often align more closely with Beijing on diplomatic issues. - Military Optionality

Ports built for trade can facilitate naval operations in crisis scenarios. - Erosion of U.S. Maritime Primacy

While the U.S. Navy remains unmatched, China’s global port access challenges America’s logistical supremacy. - A Long Game

China’s strategy is generational, not electoral—a significant advantage over democratic rivals.

Conclusion: The New Map of Power

China’s global port network is neither solely an economic tool nor purely a geopolitical weapon. It is a structural reconfiguration of the world’s maritime system—one that shifts influence through infrastructure rather than ideology.

In building ports, China is building power: steady, physical, enduring power that shapes the movement of goods, the behavior of states, and the strategic landscape of the 21st century.

As the world navigates an era of competition between great powers, the most consequential arenas may not be battlefields or diplomatic halls, but the harbors and shipping lanes that silently sustain the global economy. China has understood this for years. Its rivals are only beginning to catch up.